Perched on a grassy ridge in the sand hills of the Nebraska Panhandle, I experienced two and a half minutes of pure wonder with the three people on earth I love most. I hope they all remember it as vividly as I do, because wow what a moment to share. I say it’s indescribable, but I’m going to hack my way through it anyway.

Planning

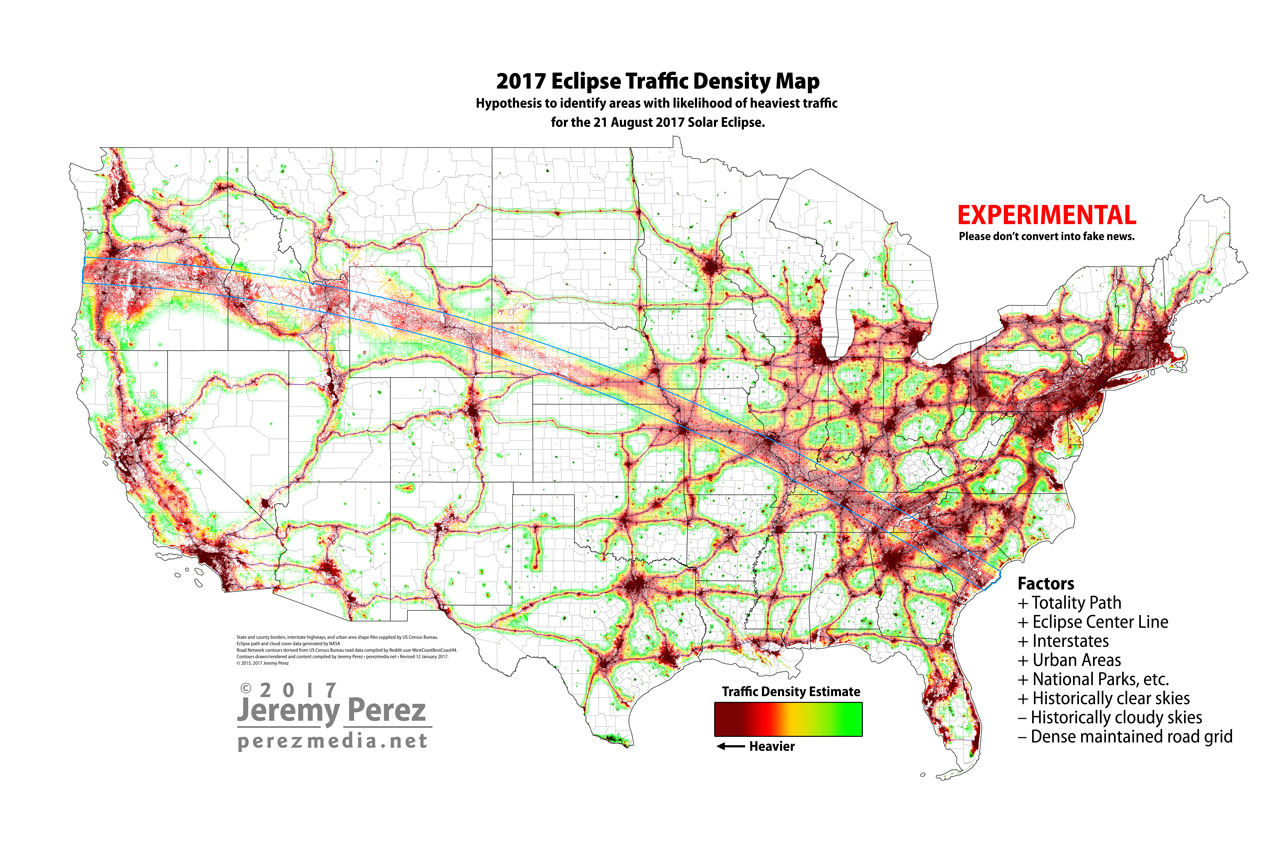

I’ve been thinking about this eclipse for years and then planning for it in the months, weeks and days leading up. I drafted road network and climatology maps, lingered on Google Street View, read reports of eclipses past, pondered doom-n-gloom predictions for gridlock, made lists, built binocular filters, and stewed over budgets. As an agonizer, this is how I roll.

For the last couple years, I tossed around the idea of sketching it—for astro stuff, that’s always been what I do. And I love that. But I couldn’t shake the thought that for such a rare, powerful and fleeting event, I didn’t want to be locked into a practical frame of mind. For two and a half minutes, I just wanted to revel in it. Which is why I definitely planned not to photograph it either.

Until a couple months ago.

I started reading more about scripting and automating shots—something that would run the exposures with minimal intervention. If one practiced and got set up early enough, it might just work. I’m a front loader, so the idea hooked me. During the lead up to the eclipse, I worked out a script using Solar Eclipse Maestro and then budgeted about an hour of fidgeting and setup before first contact. After that, it was just letting the cameras do their thing and and popping a filter off before totality (and back on after). And it actually worked. I’ve got more details in a techno section after this post.

The Trip

Our long road trip took us 1,060 miles from Flagstaff to Broken Bow, Nebraska. The days leading up were converging on a very cloudy forecast for much of Nebraska and I was seriously worried. At our overnight stop in Burlington, Colorado, I almost considered bailing on Broken Bow the night before to get the closest thing available to eastern Wyoming—basically Rapid City, South Dakota. That would put us closer to cloudless areas the morning of the eclipse, but it would also amount to staying overnight outside the path of totality…with scarce road options if there was a huge traffic problem. I just couldn’t work with that option. So we kept on for Broken Bow and planned for a very early drive the next morning, westward along the path of totality.

We woke early. Very early. And hit the road at 4AM. The forecast looked a bit better by then, but clouds were still threatening from north and south and I just didn’t want to chance it. We drove a couple hundred miles along dark roads, heavy with fog, until sunrise started to lift the deck a ways west of Ogallala. Satellite showed the stratus layer dwindling in the far western Panhandle, and it looked like we had enough time. Traffic was gradually growing as people filtered into the area, but it wasn’t gridlock. Scottsbluff was about the worst it got, but was mostly just like a heavy rush hour situation along the main drag.

We took the last bio break at a very crowded Maverick station in Scottsbluff, popped some Immodium to freeze the pipes up a bit, and then decided Highway 29 north of Mitchell would be the spot. Centerline was about 24 miles north of town, and I figured within 5 miles of that would be good. As we headed north, farmland gave way to sand hill country—which I think is beautiful to begin with. It was interesting to see the mix of scattered cars and then larger groups in different spots along the roadside. It was a lot like storm chasing modes—some people prefer the more isolated approach, while others like the convergence. It was probably astronomy clubs and caravaning buddies for that latter option. The best part of all was the nearly cloudless sky. No worries about cirrus drifting in from the south, and no cumulus field building in from the north. It was a massive relief to wind up in that spot after the earlier fears.

The Leadup

As we got closer to the center line, prime elevated spots and field access pullouts were mostly populated…again, a lot like storm chasing. About 3 miles south of the center line, we found our spot (42° 13.594 N -103° 47.341 W). Amanda got us honed in on a perfect flat plateau at the top of the ridge on the east side of the road. From there, we had an excellent view of the horizon from the northwest to the southeast. Nearby hills hid the rest, but this turned out to be just right. DEET was applied to pants and shoes on behalf of ticks, sunblock misted on, and chairs and snacks broken out. We had about an hour to go before first contact, which was just enough to set up the tracking mount for the tight 300mm views, and then low tripods for wide angle time lapse and video.

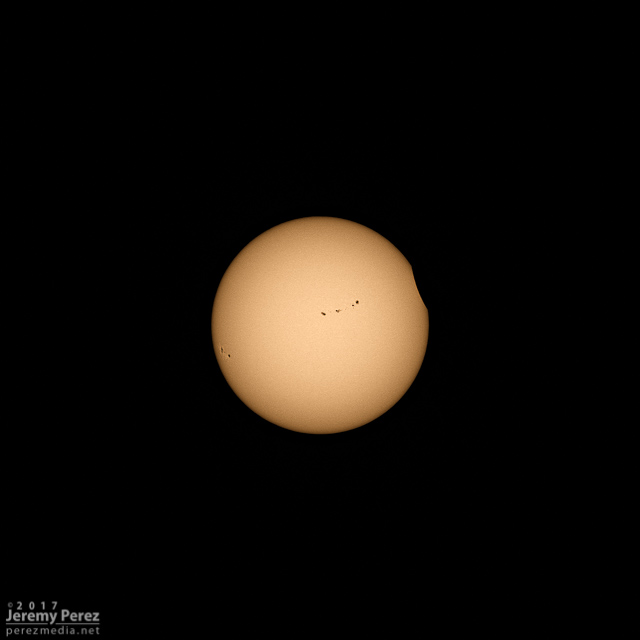

All the cameras were running and doing their thing while we hung out and watched the first moonbite expand into a perfect Cheshire Cat smile. The excited kid on the hilltop on the other side of the road was the one to spot it first and gets the prize 🙂 So cool.

Although I checked camera framing a few times, things were really running on their own. The wind was blowing at a good clip and that meant some vibration in the zoomed shots, but oh well! It would get what it would get. I got to enjoy the experience with my family. Unmagnified views through the eclipse glasses, magnified views through the binoculars where the sunspots were getting chomped away by the encroaching moon, and cross-finger crescent projections on pant legs and chair seats.

As the light grew noticeably thinner, it occurred to me that it looked a bit like old westerns where they would film in daylight and then process darker for nighttime scenes…except not black and white. It’s dreamlike. As though part of you is in a blissful, waking dream. Is this real? The crickets weren’t sure. They figured they’d better start chirping louder. It got pleasantly cooler, the wind calmed, and it got quieter—although that last part I think had a lot to do with traffic finally stopping.

Totality

In the last few minutes before totality, the light thinned quickly as the western horizon grew darker. I was a complete dork by this point, and only got worse as everything unfolded 🙂 We couldn’t discern shadow bands, and didn’t really have any solid surfaces to view them on, but I’m not disappointed by that. There was just so much to experience, absolutely everywhere, that it was a minor thing to miss. In the last moments, as the filtered crescent disappeared and the light quickly faded away, the feeling of awe, wonder, giddiness, was incredible. And then the last speck of filtered sun disappeared. As I finally looked up to see the blessing poured out on us at that very moment, I was overcome. Where the sun had just been blazing, was now a perfect black disc surrounded by pure, liquid-white filaments and petals splashing into a deep blue sky. A ruffled celestial flower, more luminous and piercingly beautiful than anything I’ve ever seen. It was bright and soft, perfect and hypnotic.

Giselle and Amanda called out the color surrounding us in the sky in every direction—pinks, purples and oranges reflecting off clouds on the far horizon beneath a deep blue canopy—an inverted, 360-degree Belt of Venus. And Venus itself was shining bright in that canopy, accompanied by a few other stars. Binoculars showed the feathers, ribbons, and ripples in the corona with a degree of detail that was overwhelming. I was gasping at this and that. Probably too much. But I couldn’t help it. After mentioning to us how it looked like a black hole in the sky, Harrison looked around and decided, “This is my new aesthetic.”. Yes. Totally that.

At some point after maximum eclipse, I realized that a couple of bright, magenta prominences were really beginning to blaze on the western edge of the disk—somehow managing to overpower the brilliant corona. I wasn’t expecting to see that with the naked eye. And the binoculars showed them much better. But this was a sign it was almost over. The sky to the west was growing brighter and the inner corona increasing in intensity behind the startlingly colorful prominences. And then suddenly the first spark of the sun flashed through the pinnacles on the limb of the moon. For the briefest moment, I had a glimpse of that spark blazing on the edge of the blackened moon with the feathers and petals of the corona still breathing sublime art into the sky. Then I reluctantly turned away and made sure everyone else had as well.

It ended too soon. I knew it would. But as fleeting as totality was, it was also bound up in time. Something that is always there now. It felt wonderful to just sit there, grinning like a doofus with my family. So amazed we had just seen the unbelievable.

Winding down

Within a minute of the end of totality, cars around us were getting back on the road. The mission to beat traffic was strong. And I can’t blame anyone for that. I’m not sure how much further north of the center line people had parked, but 70 miles of highway can hold a lot of cars. I wanted to just sit back and enjoy the experience while the highway queued up and made its conga line. We sat and talked about everything we just saw and felt, and laughed about how each of us would tumble differently if we fell off our chairs down the hill toward our car. Everyone was fine with staying long enough to let the moon drift back off the sun.

Once the last bit of moon had returned the sun to its full disc, we finished packing things back in the car. Nothing ever fits the way it did the first time you perfectly loaded it up. But with a few good mashings, the hatch finally closed. By that time, traffic had lightened up where we were, and we had a smooth drive until a couple miles before reaching Mitchell. Two miles of backup…I figured, hey, this isn’t any worse than the Broadway Curve at rush hour back in the Phoenix days. It made pretty good progress too. Turns out Mitchell, Scottsbluff and surrounding towns had planned the whole situation out and had police directing traffic flow at all the pinch points. They did an outstanding job. There were bottlenecks in a few more spots, but they all kept flowing nicely.

As we made our way to our Monday night hotel in Holyoke, Colorado, I wondered about experiencing that again. The next one in the US is 2024. Although there is one in Chile and Argentina two years from now…five minute totality…and the Argentina segment occurs at sunset. Heheh. No. I’m not made out of travel money 🙂 But still…</p.

Eclipse Photography Technical Details

Sources

- How to Photograph the Solar Eclipse — By Alan Dyer

- Observing and Photographing the 2017 Total Solar Eclipse — By Jerry Lodriguss

- Interactive 2017 Solar Eclipse Map — By Xavier M. Jubier

Software

Equipment

- Canon EOS 600D + Canon EF-S 10-22mm f/3.5-4.5 Lens for wide angle time lapse shots

- Canon EOS 600D + Canon EF 70-300mm f/4-5.6 Lens for magnified shots

- Canon VIXIA HF M30 for video

- Manfrotto and MeFoto tripods for wide angle and video support

- Orion SkyView Pro equatorial mount for stability and tracking the sun

- Baader AstroSolar Visual Solar Film for zoomed partial eclipse shots

- Neewer Intervalometers for un-scripted time lapsing

- MacBook Pro and tether cable to run the Solar Eclipse Maestro script

- Compass with declination scale and iPhone leveling app to roughly polar align the equatorial mount

- Garmin GPS for precise location coordinates (satellite based, not cell tower based)

Shot plan

Details on how to select and use a tethered scripting app are described in the ‘Sources’ links above. I finally settled on a plan to have three cameras running:

- One unfiltered camera running wide angle, intervalometer time lapse of us watching the eclipse with the sun in the frame.

- One unfiltered video camera of us watching it from the other direction with the camera facing away from the sun.

- One filtered camera running off the Solar Eclipse Maestro (SEM) script with the filter removed about 30 seconds before totality.

Preparation

The solar filter for the 70-300mm lens was made from coated construction paper and Baader AstroSolar Visual Solar Film. The Thousand Oaks Filter material is very pleasant for visual observing, but blocks too much light, requiring longer exposures and you lose detail from the blue channel and much of the green channel. Baader was just all around better for the filtered shots.

One of the key recommendations to make sure everything comes together without needing intervention is practicing over and over before the event. The SEM script requires a lot of finessing and testing. I wound up writing it to take 5 burst shots every minute during the partial phases. Then a range of exposure times in the f/8-f/9 range at ISO200 to catch the diamond ring and Bailey’s Bead effect before second contact and after third contact. Those included a 5-shot burst at hopefully the right time to get a selection of quickly changing images to choose from. Then another set of exposures to try and catch chromosphere and prominences after second contact and before third contact. Finally, two sequences of exposures during totality from 1/800 sec. to 2 seconds f/9 at ISO200 to catch a range of corona detail for blending later.

A couple places where this can go wrong is trying to pack more shots in than the camera buffer can handle. Another is getting bad GPS/altitude location entered and missing the right times for the different exposures. I decided our old Garmin GPS unit would be best for that latter part, since it tends to be accurate within about 20 feet, as opposed to cell phone GPS that I still don’t trust since it relies on cell towers. The camera buffer issue came down to testing the script on the camera over and over and changing timing until it all worked as planned.

Running the 300mm shots through a filter was another learning experience. The end of the Canon 70-300mm lens rotates as focus changes, which creates serious issues if one is careless when removing the filter, since this easily goofs up focus. So I worked out where to gaffers tape focus and zoom after getting things dialed in, and how delicately the filter could be removed and put back in place. Fortunately that all cooperated the day of the eclipse, but definitely glad to have noted how fussy it was ahead of time.

Setup of all the contraptions was another issue. I only had opportunity to practice seting it all up once, the afternoon before we left. It took about an hour to get everything put together and running and a few glitches revealed themselves in time to be corrected.

Backup Plans

Plan A was to get all three cameras set up and running. Plan B would be to set up just the wide angle and video camera shots since those were quickest and the zoomed shots would be most difficult to prep. Plan C was to just run the wide angle on intervalometer. And then final panic option—fleeing clouds at the last minute—would be to just jump out of the car and simply experience it without any pics. I feel very fortunate that Plan A worked out. But any of the rest could easily have happened…photos were a far distant second to actually experiencing it visually.