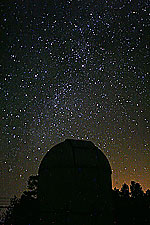

On the evening of October 30, I headed out to Anderson Mesa and set up next to Rick and Gary, a couple amateur astronomers visiting from Colorado on an observing vacation to New Mexico and Arizona. The sky promised to be spectacular as I arrived at dusk.

(Most photographs in this report can be clicked for a larger version.)

After introductions, I began my journey to spot NGC 206. A month ago, I had made a lengthy effort to observe and sketch both dust lanes in M31, and was pleasantly surprised at how much easier they were to spot right off the bat on this observation. It’s interesting how festering over an observation really stacks the deck in your favor on subsequent delvings into an object.

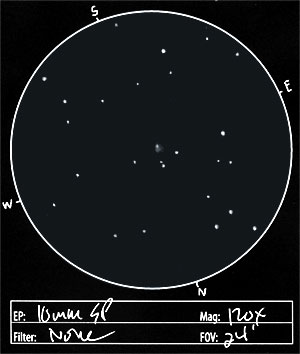

After centering my view on the correct region and inserting my 10 mm Plössl for a 120X magnification, I was introduced to an uneven appearance in the galactic disc. NGC 206 didn’t jump out right away, but after some extended scanning and averted vision, a softly brighter patch began to take shape.

Move mouse over image to see photographic overlay of the NGC 206 vicinity.

Overlay photo courtesy of: Bill Schoening, Vanessa Harvey/REU program/NOAO/AURA/NSF

Drawing an imaginary line between a bright 7th magnitude star (SAO 36585) along the east edge of the view, through the center of a north-south trio of stars in the center, drops you right into the star cloud about the same distance away on the other side. After shading in the star cloud into the sketch, I spent some time hinting in my perception of brightness variations in the galaxy itself. In particular I noticed a dark bay south of NGC 206, a brighter patch along the southwest side of the view, as well as some other broad swaths of uneven brightness. The rollover image on the sketch shows that I was able to pick up some of the general aspects of the dust bands in the area, but it wasn’t as precise as I would like.

After the observation I took a break and chatted a bit with my observing neighbors, when we were all treated to the first of several startling bolides that streaked away from Taurus that evening. As though summoned by the event, Brian Skiff suddenly appeared out of the dark surroundings to ask if we had witnessed the fireball. He kindly invited us to the LONEOS observatory for a tour and explanation of his work on the Near Earth Object survey. It was an unexpected honor. He took Rick and Gary back first while I kept an eye on the equipment and moved on to my next observation. About 45 minutes later, the two of them made their way back, and Rick led me back to the observatory.

The walk to the observatory illustrated the difference thick stands of ponderosa pine can make on available light. Out by our telescopes, starlight and some meager light pollution from Flagstaff illuminate the surroundings sufficiently for easy navigation without red flashlights. But beneath the trees, along the narrow observatory road, things are much darker and I nearly fell down an embankment at one turn. As we approached the observatory, soft, intermittent whirrings emerged from the dome. The telescope was busy snapping up images of the populous sky. Immmediately inside the first door, Rick rapped on a second door and then left as I entered the warmly lit interior of the LONEOS control center. Brian took over from there and gave me an overview of the technology and procedures he follows to locate undiscovered asteroids, some of which potentially cross Earth’s orbit.

In this photograph, Brian sits to the right, describing the process. The green monitor in the center details the telescope control and status. The workstation on the left allows him to enter coordinates for ongoing image batches. It also displays the large images coming in from the telescope. The workstation on the right displays cropped sections of those larger images. Suspicious objects are hilighted by a green circle, and data is supplied that lists rough magnitudes and motion for these objects. The majority of these ‘finds’ are false positives, such as galaxies on the edges of the frame, diffraction spikes from bright stars, random noise and the like. But there are still a great number of real orbiting objects being picked up. It’s Brian’s job to tell them apart. When a real object is found, it is compared to orbital data in a database to determine whether it has already been catalogued. This all happens very quickly. The man is fast. On an average night, he may have to sift through over 1200 images, picking out the important bits for further study. Some nights, though, that number edges toward 5000! When an object doesn’t match up to any existing orbital data, it is sent off to the Minor Planet Center for further analysis and cataloguing. The survey is averaging one unique, new object per week. This evening while we were there, the imager coincidentally captured the asteroid Hermes. This was an asteroid that was originally photographed in 1937, and then was lost for 66 years before Brian rediscovered it in 2003. And it had come back around on this night for a brief cameo.

In this photograph, Brian checks and marks off coordinates of the sky that need to be imaged, or have already been imaged. The LONEOS project concentrates mainly on the area around the ecliptic while skipping the crowded regions of the Milky Way (the inverted U-shaped gray band).

Brian was a gracious and informative host, and I really appreciate the time he took to show us the ropes. As we exited the dome, the constellation of Orion slapped me across the face with it’s brilliant angles. I thanked Brian, and headed back down the road to my waiting telescope. I couldn’t help but snap some photographs of the other observatory domes along the way. As I made my way back I also caught my second bolide of the night streaking down near Polaris. According to Gary, a couple more had lit up the sky while I was inside the observatory.

Back at my scope, I continued my search for the M31 globular, G1 (Mayall II). The excellent finder charts provided in Sue French’s article led me straight to the right spot. What showed up at G1’s location came across as a soft, nonstellar patch at 120X magnification using a 10 mm plössl. At odd intervals, I got a hint of stellaring in the midst of this haze and indicated that in the 120X sketch.

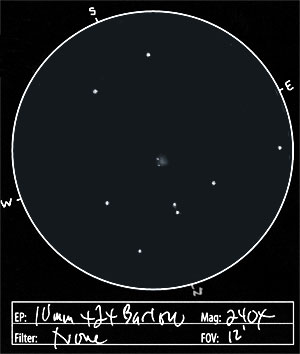

My initial impression was that I was seeing the globular cluster even at this low magnification. But I recalled a caution from observers at the Cloudynights.com forums that to really call the observation a done deal, you need to be able to split the cluster from two very closely associated, faint stars (well…faint for a 6″ scope I suppose). So I inserted the 2X barlow to bring the magnification up to 240X.

At this point, I was working with a seriously faint image, and as wonderfully dark as the sky was, I still had to pull the hood of my jacket over my face and eyepiece, and breathe deeply to try and locate these two stars. I hadn’t carefully studied Sue’s actual sketch in the article ahead of time for fear of prejudicing myself for an averted imagination experience. But I did know those two stars would be close enough to give a Mickey Mouse head appearance to the cluster. Folks, I had already spent 45 minutes on the search and sketches up to this point, but I had to spend another 45 minutes more trying to coax these last 2 stars out. I think I was setting myself up for frustration in a way, because seeing was really very poor, and stellar glimmers popped up only very very briefly, at aggravatingly lengthy intervals. Over the course of that 45 minutes, one star toward the southern side of the fuzz patch popped up a number of times. But only on 5 occasions over that time span did both stars momentarily flicker into view. They were lined up roughly north-south along the west side of this tantalizing blot of haze. I marked them in the 240X sketch, but that sketch really needs to be animated to show those two naughty stars flickering into view for 1/10 of a second out of every few minutes. I think that may be infrequent enough to call this a questionable observation, but I am intrigued enough to try again if I get a night of less than vengeful seeing at one of our nearby dark sites.

I had wanted to make an observation of one or two mid-sized dark nebulae–Barnard 5, 34, or 35, whichever gave themselves up first. But a stiff breeze began to envelope the site, and I didn’t have the patience to deal with it. It was edging up on 1 am anyway, and I needed to get to work in the morning. So I packed it all up, said goodbye to Rick and Gary, and headed on down the road. It was really a very productive evening by my standards. Two challenging observations covered, fiery bolides, and a front row seat to the hunt for near Earth asteroids. The tough part is remembering it and writing it all down. I hope you enjoyed.